Today, digital technologies are omnipresent in the lives of many Europeans. As the region grappled with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, it experienced a ‘digital migration’, with digital adoption among consumers jumping from 81% to 95%. Over the past decade, the region has seen continued growth in most areas of ICT infrastructure, access, and use. Mobile cellular coverage is estimated by ITU to be close to 100%, and active mobile broadband subscriptions reached 99.9 per 100 inhabitants in 2019, surpassing the world average of 75 per 100 inhabitants. Further, the region exhibits the most affordable mobile-data relative to income. The European Union is also considered to be a leader in data privacy regulation, shaping global standards through its creation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Understanding local and regional contexts

The Europe region continues to lead the NRI rankings, representing 17 of the top 25 countries in 2022. The rate of connectivity is also high among young people, the centerpoint of this year’s NRI theme, with 96.2% of 15- to 24-year-olds using the Internet, well above the world average of 69%.

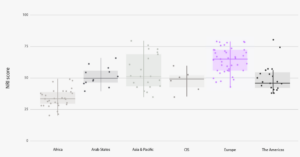

However, differences can be noted in the respective readiness of some European networks compared to others, as demonstrated by the relatively large variation of scores in Figure 1. The digital contexts experienced by ‘digital natives’ also differ across the continent, depending on a number of factors discussed later in the article.

Northern European countries like Sweden (3rd), Denmark (6th), Finland (7th), and Norway (10th) have generally topped the overall NRI rankings. These economies also notably dominate the Governance pillar due to their sophisticated ICT regulatory environments. Repeatedly, what makes the performances of these economies stand out are (i) consistently strong showings in most, if not all, dimensions of network readiness, and (ii) a focus on ensuring that technologies are tangible and accessible. These economies take the lead on implementing regulatory frameworks, and adopting new technologies like AI, robotics, and IoT. They also lead in expanding Internet access in schools and promoting ICT skills in the education system.

Several Central and Western European countries, such as the Netherlands (4th), Switzerland (5th), and Germany (8th) have also paved their way into the top 10. This region has been characterized by technological innovation since the twentieth century, prioritizing investments in operational technologies to advance competitiveness against leading industrial nations. Like Northern Europe, the region is home to a digitally skilled population, with over 60% of inhabitants achieving ICT skills at or above the basic level in most countries. One of its largest economies, France (16th), stands out as generating notable impact as a result of its participation in the network economy due to its activity in high-tech and medium-high-tech manufacturing, and focus on urban sustainability. Austria (18th) sets an example for digitally engaged businesses and government, and renewed focus on digital inclusion. Luxembourg (17th) is a global leader in the Regulation of technologies, while Ireland (20th) continues to champion SDG contribution. The United Kingdom fell from the top 10 group for the first time since 2019, down to 12th, due in part to lower output in regulation and privacy protection. However, the country is working on robust data protection legislation, the Data Protection and Digital Information Bill, which is scheduled to be adopted in 2023.

Economies in Southern Europe display notably balanced performances across all dimensions of network readiness. Spain (26th), the highest-ranking Southern European economy, excels in ensuring ICT access with renewed focus on closing urban/rural and socioeconomic gaps, particularly for transactional technologies. It is also the only European country where men and women are using the Internet at equal rates. Italy (32nd) performs notably well in the SDG contribution and Economy subpillars, as well as improving its performance in Future Technologies and Access. However, for both countries, room for improvement remains in the production of digital content, public trust in digital technologies, and the social impact of the network economy. Greece (49th), though a global leader in tertiary enrollment with a highly digitally skilled and engaged population, lags behind the region overall. In particular, its low levels of investment in emerging technologies and barriers to digital access place the economy at a disadvantage.

Eastern and Southeastern European economies, particularly the Balkan states, continue to lag behind the rest of the continent in network readiness, especially when it comes to investment in and adoption of emerging technologies. The onset of the COVID pandemic highlighted ongoing structural and connectivity challenges in the region, reflected by low active mobile broadband subscription counts and high tariffs on ICT goods. The shift to online learning proved to be challenging as well, due to inadequate digital equipment and generally low levels of ICT skills among segments of the population. While some economies have begun adopting e-government services and financial technologies and applications, accessibility remains an issue, as demonstrated by large rural gaps in digital payments, gender gaps in Internet usage, and difficulty accessing online financial accounts. Further, increased internet traffic also presents digital security risks, especially for vulnerable populations.

However, there are bright spots emerging, especially in the area of Governance, where the region has seen marked improvements. Estonia, a trailblazer in digital innovation, ranks 6th in Governance and 3rd in Trust. These developments have been crucial towards achieving global leadership in e-participation, and setting an example when it comes to digitizing government services.

Outperformers bridging the gap: the case of Ukraine

Generally, high income economies outperform low and middle-income economies in the network readiness rankings. However, one European country is closing this gap: Ukraine. Ukraine (50th) has risen in the rankings (by 3 positions), one of only 7 economies in Europe to do so this year. It is the highest ranking lower-middle income economy, and the only one to appear in the top 50 this year. Ukraine also stands out as performing above expectations given its income level in the Technology, People, and Governance pillars.

Note: Data underlying the NRI do not refer to a single year but to several years, depending on the latest available year for any given variable. Therefore, these results reflect the performance of Ukraine during the pre-war period.

Behind the trends: the factors shaping European network readiness

The ongoing persistence of the disparity between North, South and Eastern Europe in relation to network readiness could be, on the surface, attributed to the well known gap in economic fortunes between the three regions. In this context, the EU economy can be grouped in three macro groups, a slower group represented by Western Europe, high-speed nations of formerly Communist Eastern Europe, and a third group, the South. Since 2015, 1.5 billion euros in EU funds have been employed to support digitalization interventions across multiple European countries. Between 79% and 99% of these were dedicated to infrastructure and technology implementation, including widening the access to e-services and broadband. Overall, from 2016, the EU Member States planning the largest investments in ICT were Poland, Italy and Spain, which occupy significantly lower places in the NRI ranking compared to Nordic European countries. Although economic factors play an important role in determining the countries’ position in the NRI ranking, organizational factors are equally important to ensure effective preparedness for digital transformation within a country. It is possible that, despite large investments in ICT, the strategies applied by Southern and Eastern European countries are not ultimately bringing concrete improvements in the longer term. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of more balanced profiles across all NRI pillars, suggesting the absence of a uniform approach to effectively implement allocated funds. On the other hand, Nordic countries consistently top this year’s NRI, ranking among the best performers in every pillar category.

When considering the various factors influencing this year’s NRI ranking, one must also take into account the transition between the state of emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic and the slow return to normality. Overall, it could be concluded that, despite the initial state of alarm and then stillness of the pandemic, the development of the digital infrastructure significantly benefited from the need to move the large majority of activities to an online environment. Nevertheless, as the world is mostly returning to normal conditions, the NRI highlights minor yet interesting drops of 2 to 3 places for a significant number of high income economies like the Netherlands, Finland, Belgium, and the UK. While at this point we can only speculate on the reasoning behind this trend, the instability of the global landscape has certainly shaken the structural weaknesses of the European context. In fact, the ongoing war in Ukraine could be seen as one of the main catalysts for the slowing down and even slight regression in digital development experienced by prominent highly performing European countries. In this context, causal factors stemming from the conflict can primarily be grouped into: (1) the reallocation of funds once aimed at the broad development of the digital infrastructure and, (2) the structural weaknesses of the European energy market. In particular, the second point highlights a significant gap in European network readiness: the insufficiency of green energy funds to sustain the energy transition. In fact, investments in renewable energy had already suffered a decline due to the reallocation of funds throughout the Covid-19 pandemic which, coupled with an over reliance on the Russian Federation as a gas supplier, have ultimately resulted in a growing gap between demand and supply and the interesting phenomenon reported in the NRI.

While it is still difficult to forecast the full spectrum of repercussions that the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine will have on digital development and readiness in the long term, the NRI results can aid in outlining a first picture of their effect in the post-emergency context. Through the analysis and discussion of the NRI data for the European area, we can offer, above all, a recommendation for the region to focus future policies and interventions on the efficient strategic planning of resources and investments as found to be the strongest indicator of an effective and long-lasting digital readiness and resilience. Importantly, the energy crisis should not be treated as a secondary issue as its repercussions echoing across a multitude of domains, may ultimately lead to the loss of previously made advances and the resources that made them possible.

Claudia Fini is a Senior Fellow at Portulans Institute and an Associate Researcher at the UNESCO Chair in Bioethics and Human Rights based in Rome, Italy, where she has analysed the ethical, legal and public policy challenges of artificial intelligence with a focus on human rights and sustainable development goals. She is passionate about trauma-informed policies and practices that will make the transition to a digital society safer and more effective for all populations. Claudia holds a BSc in Neuroscience from King’s College London and an MPhil in Criminology from the University of Cambridge.

Sylvie Antal is a Policy Research Associate at Portulans Institute with prior experience in digital privacy issues relating to minors and vulnerable populations, as well as in consumer education and technology for international development. Sylvie holds a bachelor’s degree in Information Science from the University of Michigan’s School of Information where she was a member of Tech for Social Good, and a Masters degree in Human-Computer Interaction.