With every new generation of technological development, the baseline level of expertise necessary to competently master technological instruments increases. Importantly, a sufficient degree of digital competency (expressed by the above-mentioned baseline level) has now become essential to living in a growingly digital world. The natural consequence of this phenomenon is the ever-growing need for new knowledge and skills. Raising costs and complexities can widen the social and economic divisions between those who can afford to stay on track with the digital transformation, and those who are unable to keep up with technology advancements. While the concept of the digital divide has been extensively discussed, the issue of age as a key player in this divide, has only started to be addressed. In its current state, the education system largely takes digital skills for granted. On one hand this approach is not without consideration: students from all educational levels are certainly more digitally skilled today than youth even five years ago, due to the growingly pervasive presence of technology in our everyday activities. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased the demand for digital skills for those participating in remote learning activities throughout the course of quarantine. Nevertheless, a common denominator across youth from all educational levels is that technological skills are being largely learnt homeostatically. In other words, digital learning is acquired indirectly from everyday interactions with the digital world, rather than being developed through an appropriate educational curriculum. These considerations open two sets of problems respectively: (1) some students are left without properly developed digital literacy skills, which are often taken for granted or assumed, thus facing severe setbacks in academic progress and success, and (2) those who are able to develop digital skills on their own face the very pervasive challenges of digital naivety, which are characterized with the lack of judgement and awareness of their and others digital presence. In this context, both (1) digitally uninformed and (2) digitally naive youth are at high risk of manipulation, both in terms of content or information (e.g., filtering fake news) and in terms of communication channels (e.g., where to find relevant and reliable information).

In an increasingly digital ecosystem, nations should start to focus on the importance that digital education will have in the near future and develop policy actions accordingly. Some countries have already started to introduce digital policy initiatives with a clear impact for digital education. For instance, Finland made broadband internet a legal right in 2010, and in France the constitutional council ruled in 2009 that internet access is a human right. Similarly, broader initiatives have been taken by the UN Human Rights Council to recognize and promote access to the internet as a human right.

Despite these outstanding initiatives, the global digital landscape remains largely fragmented. Within the European context, for instance, the Network Readiness Index identifies Bulgaria, Romania and Greece (respectively ranked 50th, 47th and 46th in the global NRI ranking) as significantly lagging behind the most network-ready digital economies of the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark, which reach the highest scores in the index not only among European countries, but globally. If the promise of quality education for all is to be maintained, broader network-wide initiatives should be developed. Keeping the European context as a primary example, a first step has been taken by the European Commission in late January 2022 with the European Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles for the Digital Decade, a set of guidelines proposed as a framework for the future development of digital transformation. The Declaration focuses on fundamental rights, data privacy, and the protection of stakeholders seeking to promote human-centric digital growth. While the impact that this initiative will have on digital education is yet to be determined, building on a right to digital education, as a further specification of a right to education, could address the digital divide and digital illiteracy.

Further addressing this issue, it will be important to focus on the fact that too much information can be paradoxically dysfunctional to learning, creating a barrier to a basic thought process. In fact, simply being exposed to a gigantic quantity of information does not necessarily translate youth into informed citizens; rather youth should develop skills beyond technical, and learn how to use the large amount of information of today meaningfully. This consideration represents the very basis of the concept of digital literacy. Here, the importance of being online and being able to access online educational content and services is clear, but digital literacy also encompasses the development of digital literacy skills to enable individuals to assess and use the “most appropriate and reliable’ information needed to “make decisions about their lives”. Digital literacy takes elements from the concept of ‘information literacy’ – referred to as “a person’s ability to collect, process, evaluate, use and share information with others within her/his own socio-cultural context” – and applies them to the digital context to make informed life choices and decisions. Among these are the soft skills of critical thinking (i.e. the ability to judge and critically evaluate information sources) as well as problem-solving. Extant evidence has repeatedly shown that the lack of information literacy skills often leads to information poverty and ultimately limits the capacity of individuals to participate in society. Indeed, digital literacy skills are nowadays an indiscernible element of societal belonging and a “prerequisite for full participation in the modern, digital world”.

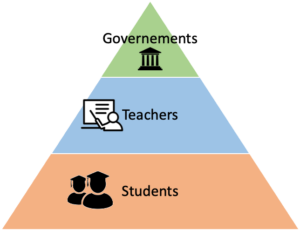

The development of policy initiatives for the use of digital technologies in education requires the provision of a strategic vision including governmental guidance and support as well as training for teachers and students. The diagram below identifies these three key steps. First, governments need to provide tangible support to allow all regions to possess the digital education infrastructure. Second, policies must be driven by the awareness that digitally unequipped regions would most likely display a large pool of digitally untrained professionals. Teachers are the connecting link between government and students, acting as planners, facilitators and guides for the effective implementation of the curriculum. As such, developing appropriate policies aimed at teacher training and development is necessary. This need has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as physical learning has been forcefully transferred to a virtual space. Lastly, the student body represents the ultimate target of digital education policies.

To foster the dialogue on digital skills and their relevance within the higher education context, Portulans Institute has partnered with the UNESCO Chair in Bioethics and Human Rights and IIASA. Our partnership has taken the form of a policy brief titled “Building a digitally ready education system with a bioethical framework – the new normal” and has been submitted to the UNESCO World Higher Education Conference 2022 that will take place in May in Barcelona, Spain. Our policy brief highlights the importance of building up digital skills as a primary response to the recent digital turn within the labour market, especially in the post-Internet phase. In many ways, the focus on digital skills seeks to explore and understand emerging forms of work, evolutions in the labour market and the challenges and opportunities resulting from it. Research interest in digital skills has increased exponentially since 2016 and focused primarily on (1) industry (e.g. Industry 4.0, skills, digital technology, job transformation, etc.), (2) capacity development in the workplace, and (3) educational processes and skills that need to be developed for Industry 4.0.

Following the main theme of the conference, our policy brief focuses on this latter category, essential to prepare young learners for the upcoming challenges of the digital ecosystem. In this context, a recent “digital turn” has been witnessed in a wide variety of disciplines including economics, architecture, and communication, highlighting the progressive academic interest in developing new models of human’s ability to create, exchange, and apply concepts and resources. Beyond the mere academic interest in the digital reinvention of disciplines, it is necessary for education and training institutions to employ practical approaches to respond to the evolving occupational profiles and skills requirements.

In this context, bioethics is essential for developing critical thinking skills and the development of a dominant knowledge paradigm, instruments that will assist any individual in determining the optimal values, norms, and moral rights to resolve current and future social issues. Certainly, the subject of technology is particularly suited for the application of a bioethical framework, as a rapidly developing field accompanied by equally rapidly evolving ethical challenges in relation to protecting privacy, information ownership and practical applications. This is an especially urgent task for regions that are lagging behind several cycles of digital developments. In this sense, the establishment of a solid learning structure could be capable of responding as rapidly and effectively as possible to the ever-evolving labour market. However, this is also important for regions with high investments in tech, as the digital skills of citizens may be taken for granted and assumed at an adequate level.

— Claudia Fini

Claudia Fini is an Associate Researcher at the UNESCO Chair in Bioethics and Human Rights based in Rome, Italy, where she has analysed the ethical, legal and public policy challenges of artificial intelligence with a focus on human rights and sustainable development goals. She is passionate about trauma-informed policies and practices that will make the transition to a digital society safer and more effective for all populations. Claudia holds a BSc in Neuroscience from King’s College London and an MPhil in Criminology from the University of Cambridge.