This blog post is part of a series where Portulans staff perform a more in-depth analysis of countries and regions covered by the Network Readiness Index.

Digital is the keyword of the COVID-19 crisis. The Africa Report notes that in the past few months, “digitizing has moved from a good to have, to a survival game-changer in what has become the new norm.” For headlines on Africa, the keywords that closely follow digital are catalyst or kickstart. Many onlookers note that the necessity of digitization has provided the essential trigger for a digital revolution in Africa.

However, Africa’s digital economy was not initiated by the pandemic, explains Eric Osiakwan, Managing Partner of Chanzo Capital. Why? The African digital economy is already well-established. The more recent leaps in e-commerce, mobile payments, digital media consumption, and connectivity are possible thanks to the foundations laid in the past two decades. If anything, argues Osiakwan, the conditions created by COVID-19 have accelerated patterns and trends already in place, at an unprecedented pace.

Yet these trends are neither uniform nor straightforward. And amid the COVID-19 crisis, they hold both obstacles and opportunities for Africa’s digital economy.

Africa’s Digital Economy

As Osiakwan comments, in the past two decades, the continent’s digital economy has been made possible due to leaps and jumps by Africa’s KINGS (Kenya, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa). These countries have created an “unstoppable wave of technological innovation” for the African continent. Beyond Africa’s KINGS, the digital economies of Rwanda, Egypt, Tunisia, Mauritius, and Morocco are also known for their growth, supportive tech infrastructure, and ecosystems of innovation supported by legislation (public sector) and an entrepreneurial spirit (private sector).

Across Africa, and particularly in these ten highlighted economies, the growth of the digital economy has shown the potential to transform anything from elections to agriculture. Kenya is known as the “Silicon Savannah” and witnessed its ICT sector to grow an annual average of 10.8% since 2016. The launch of mobile money (M-PESA) in 2006 paved the way for the growth of companies like Cellulant, at the forefront of Africa’s rapidly emerging and incredibly popular mobile money transfer economy. Rwanda’s capital Kigali is a hub for innovation; and, most government services are available online via the Irembo citizen e-service portal. Following its digitized of 2011, Tunisia has emerged as an aspirational tech hub, too, particularly following the Start-Up Act of 2018 and newfound investment and inspirations from the private sector, innovative, youth-led tech start-ups have skyrocketed.

As a civil engineer and the co-founder of social enterprises WomEng and WomHub, Naadiya Moosajee notes, “necessity is the mother of invention, and in Africa, it has been the mother of innovation.” Africa’s digital innovations have been developed in response to the continent’s most significant issues, such as e-healthcare and online education solutions. “For the first time, we are seeing a trend of being technology generators rather than just adopters.” In many cases, Africa’s youth (the “Cheetah Generation”) is at the forefront of innovation.

Africa’s digital potential has not gone unnoticed by big tech. Leading figures across Microsoft, Facebook, Alibaba, Google, and Twitter have visited start-ups and local entrepreneurs across the continent. In May 2019, Google launched its Africa Development Centre and its first AI lab in Accra, Ghana. Multinationals in communications (Vodafone), energy (General Electric), and e-commerce (Jumia) have significantly expanded their operations in recent years.

Limits to Innovation

Despite the impressive track record of improvement of Africa’s digital economy, onlookers must be wary not to rely on continental generalizations that overlook the uniqueness of regional, national, and local digital developments or, in some contexts, the lack thereof.

First of all, Africa’s digital revolution is not continentally uniform. From 2014 to 2018, 130 million more Sub-Saharan African mobile users were connected to mobile internet. Yet gaps in coverage and access remain. As the Global Innovation Index (GII) indicates, ICT access, use, governmental online service, and e-participation (Indicator 3.1) are higher in North Africa than in Sub-Saharan Africa. Mauritius leads the continent in ICTs (66th, 66.3), followed by South Africa (67th, 66.3), Tunisia (69th, 65.4), Morocco (74th, 62.5) and Ghana (86th, 54.5). There is much regional disparity: Burundi (126th, 22.9), Malawi (127th, 20.4), and Niger (128th, 18.7) are among the lowest-ranked.

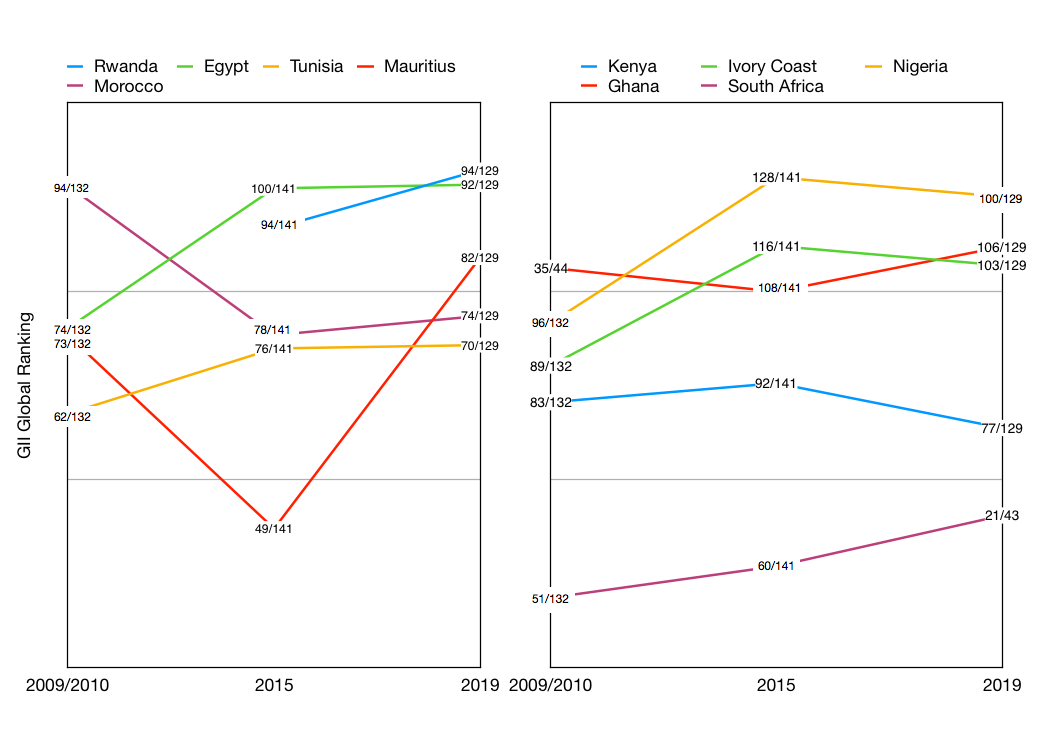

Even within Africa’s stronger digital economies, there are limits to the uniformity of digital development and innovation. For instance, the GII analysis demonstrates that the ten highlighted economies’ relative global rankings have not significantly improved in the past ten years.

Figure 1. Global Innovation Index Rankings 2009-2019*

*Relative ranking indicated in data

This is a picture that requires more in-depth analysis through indicator-level analysis, supported by insights from the Global Talent Competitiveness Index and the Network Readiness Index. Together, these three indexes allow onlookers to delve deeper into the nature of innovation in the region.

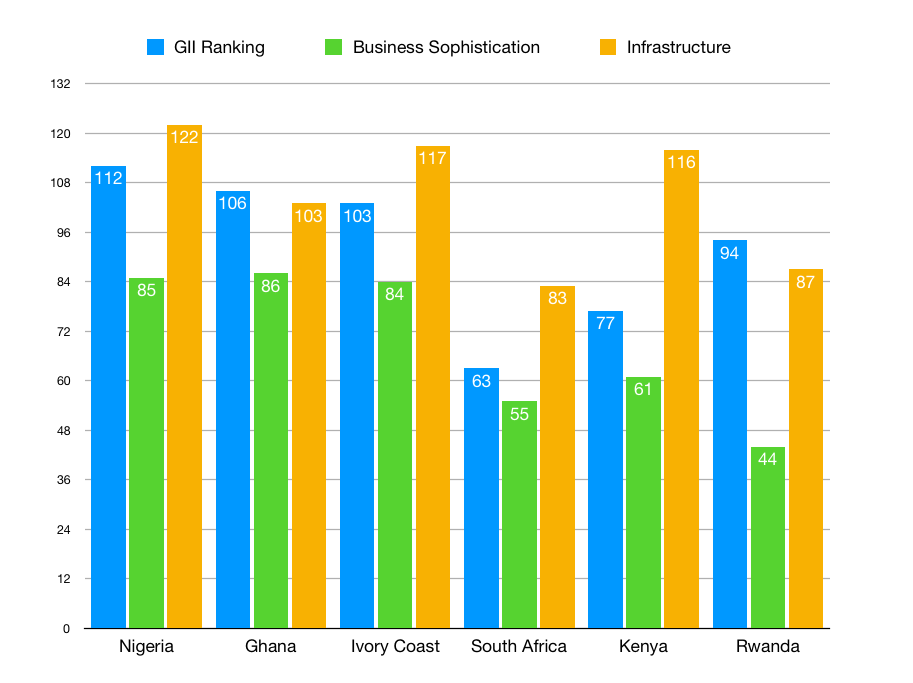

For Africa’s KINGS and Rwanda, the energy to innovate is not yet supported by infrastructural capacity to innovate. This trend can be displayed by a comparison of two GII pillars, namely Infrastructure and Business Sophistication. While the Infrastructure pillar considers ICTs, general infrastructure, and ecological sustainability, Business Sophistication takes into account knowledge workers, innovation linkages, and knowledge absorption. In all cases, rankings for Business Sophistication are significantly lower than for Infrastructure.

Figure 2. Global Innovation Index (2019)* – Infrastructure vs. Business Sophistication Rankings

*The ranking compared 132 countries

Two examples demonstrate this critical gap. For Kenya to “keep pace” with the development of its digital economy, the World Bank and Center for Global Development both report that gaps in access and skills must be addressed, particularly given the magnitude of the digital divide: while 44% of the urban population have access to the internet, only 17% of rural residents do. The GTCI notes that Kenya’s Technical and Vocational Skills (44.32, 64th) significantly lag behind its Global Knowledge Skills (14.7, 103rd), which measures higher-level skills and talent impact. For Nigeria, the NRI reveals that Access to Technology (24.82, 113th) lags behind network-ready Businesses (29.65, 64th). This is consistent with GII findings, namely that Infrastructure (26.6, 122nd) may inhibit other areas of innovation.

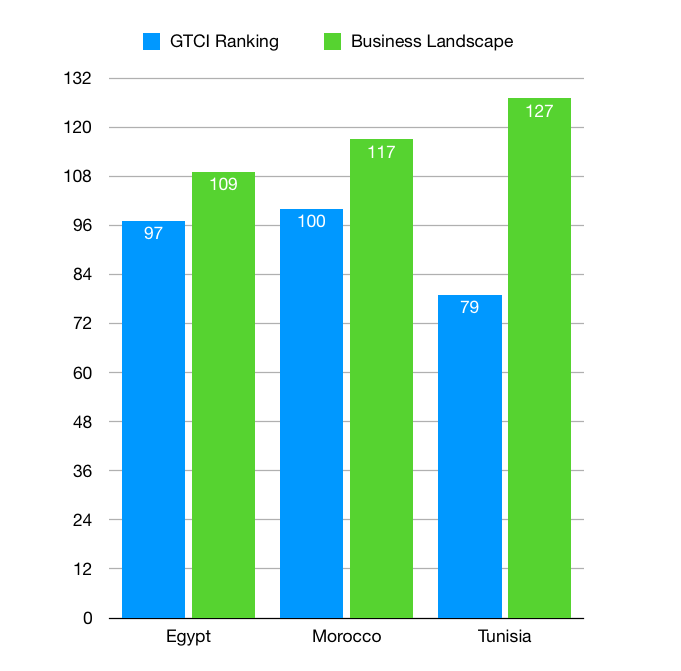

However, in three other economies (Tunisia, Morocco, Mauritius, and Egypt), the GII index demonstrates that infrastructure is consistently better ranked than Business Sophistication. For these economies, the GTCI analysis may suggest that the limit to innovation is the Business Landscape, which crucially includes measures such as technology utilization and investment in emerging technologies.

Figure 3. Global Talent Competitiveness Index (2020)* – Ranking vs. Business Landscape

*The ranking compared 132 countries.

As the World Bank Digital Economy for Africa initiative notes: “Africa has the opportunity to harness the digital economy as a driver of growth and innovation, but if it fails to bridge the digital divide, its economies risk isolation and stagnation.” In addition to infrastructural weaknesses and deficiencies in the business landscape, many digital developments and innovations are stifled by strict legislative and political environments. Affordability and access continue to spark frustrations; in 2019, Zimbabwe blocked Internet connectivity in response to domestic unrest. Freedom of expression and access are not guaranteed in many of Africa’s young democracies and non-democratic countries.

Therefore, the main limitation to optimistic thinking about Africa’s digital economy is that the innovative wave started by Africa’s digital economies is not yet a continental phenomenon. Countries without an enabling public sector and thriving private sector may be excluded or left behind the curve of digital transformation. While the growth of Africa’s digitally-ready countries is highly encouraging, building a multistakeholder digital economy with advanced network readiness is no doubt a long and arduous process, exacerbated by the crisis.

Gauging Africa’s Digital Readiness for COVID-19

Based on this analysis, a dual understanding of Africa’s digital readiness for the consequences of COVID-19 emerges.

On the one hand, Africa’s digital economy is remarkably more well-prepared for disruption than many onlookers give it credit for. By many measures, the crisis is necessitating digital transformations that will indeed speed up Africa’s digital economy, such as the growth of e-commerce, mobile money transfers, online learning, improved affordability, and increased accessibility. Although many public sectors have, in the past, lagged behind the curve of private sector-led digital innovation, the realities of COVID-19 have awakened them to the necessity of digital transformation. For instance, Ghana’s Ministry of Education announced the use of online learning platforms in March; in April, Equatorial Guinea’s Infrastructure and Telecommunications Ministry announced increased bandwidth speed and connectivity in response to the crisis.

On the other hand, the World Bank projects that the crisis will plunge a further 23 million people into extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa alone. Two-thirds of people in 20 African countries fear to go hungry if forced to quarantine for weeks on end. Perhaps it will take decades before scholars and policymakers can gauge the far-reaching consequences of the crisis on African lives and livelihoods. Yet it is already evident that regional variations in digital readiness have a potentially major impact on both counts. Besides, even though the use of tech-based solutions by some African governments is hopeful, it is an example of need-based digitization as opposed to future-ready digital transformation.

Looking Ahead: Three Digital Trends

It is clear that digital readiness and investment in digital infrastructure is essential for handling the crisis. For instance, a recent UN policy dialogue noted that Egypt’s digital readiness has enabled the country to minimize disruptions to education and healthcare. Egypt’s e-learning platforms are capable of handling up to one million students sitting exams simultaneously. At the same time, the country’s broadband network has been mobilized for e-healthcare solutions to primary care units.

In the next few months, regional and international policymakers should study and draw lessons from how African governments, firms, and networks leverage the digital economy’s tools to bolster regional, national and local pandemic responses. From a digital transformation standpoint, three particularly exciting trends warrant attention and further study.

First of all, youth-led innovation is more critical now than ever before, and is increasingly leveraged by digital platforms. Africa has the world’s largest youth population; around half of its population is under the age of twenty. As public policy analyst Raphael Obonyo notes, youth is vital in the fight against COVID-19; they “represent energy, creativity, and innovation.” Regional and international organizations recognize this potential. Since last April, the Youth Alliance for Leadership and Development in Africa and the World Bank’s Youth Transforming Africa Initiative has held regular online roundtables on how Africa’s youth can respond to the COVID-19 crisis. At a national level, in Rwanda, Youth Voices Rwanda leverages social media networks to coordinate these responses.

Youth-led innovations are taking leaps and bounds, particularly for online learning. In Cameroon, youth entrepreneur Angele Messa launched EduClick, a company specializing in online learning methods for students unable to access education due to poverty, violence, or, more recently, the pandemic crisis. And in Tanzania, George Akilimali’s Kisomo SmartLearn app provides high-quality digital education in local languages Swahili and Bantu.

In addition, public-private sector collaboration in the digital economy is witnessing newfound attention and has increased consequence. In South Africa, the government has partnered with Vodacom to provide citizens with advice, information, and assessment tools; the government has also leveraged WhatsApp as an interactive chat service to answer questions about COVID-19. In Tanzania, Wellvis company, an online health information platform, has created the COVID-19 Triage Tool to enable individuals and firms to self-assess their risk categories, based on exposure and symptoms. President Kenyatta has encouraged Kenyans to shift to M-PESA cashless transactions, to lower the risk of infection in transactions. To this end, Safaricom has waived fees for low-level transactions and increased transaction limits. Cryptocurrency, particularly blockchain, has received newfound interest. Integrating digital tools in the COVID-19 responses is a necessity, and the public sector across Africa is waking up to the enormous potential of firms and solutions within the digital economy.

And finally, as Wellvis CEO Wale Adeosun notes, “the approaches to our own solutions cannot be gotten from individuals who do not understand our context.” As international innovators, academics, and policymakers, we have a responsibility to learn from and encourage innovation and digital readiness in Africa. However, there is by no means a one-size-fits-all model of innovation, particularly during a crisis of this magnitude. The impact on lives and livelihoods will not hit all countries equally. Although the pandemic is a global crisis, its consequences for Africa necessitate local solutions and international support, not international solutions and local support.

By Isabella Wilkinson, with contributions from Dr. Niousha Roshani and Carolina Rossini.