Trust is an important dimension of social capital, which in turn is related to innovation and growth. This year’s Network Readiness Index Report focuses on trust in technology and the network society.

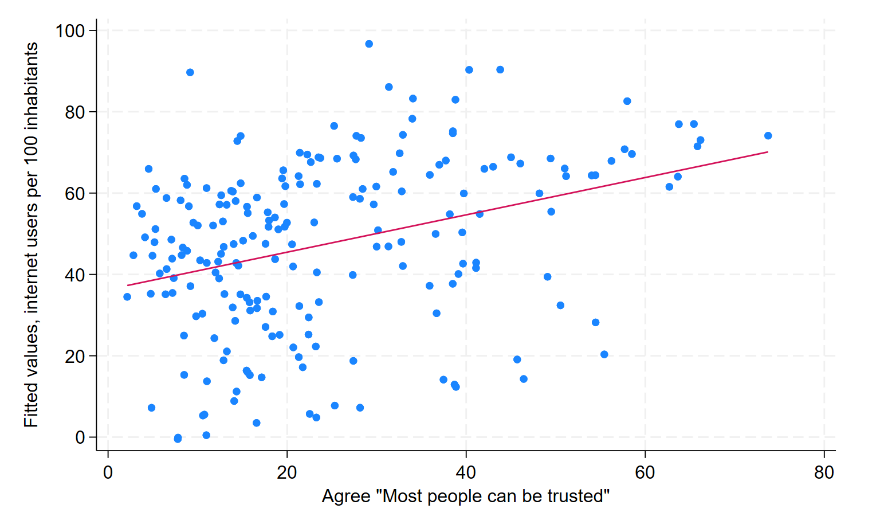

With trust, technology is more likely to be used (Figure 1). For instance, the OECD has developed principles of trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI) which have been widely adopted as metrics to assess new AI applications and systems. In the trade policy field, cross-border data flows with trust are an objective in the digital trade chapter in most modern international trade agreements.

Figure 1: Trust matters for Internet use

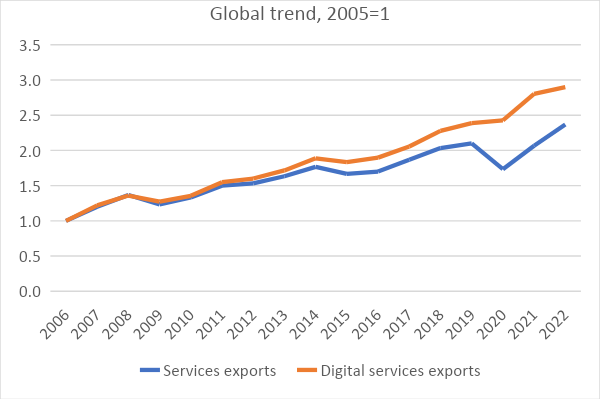

Nowhere are dataflows with trust more important than in the services economy. Digital services trade kept growing throughout the Covid 19 pandemic despite a sharp drop in overall trade volumes (Figure 2). Indeed, the rapid development and adoption of new digital platforms such as Zoom enabled people to continue to communicate, learn, access information, produce and consume during Covid lockdowns.

Figure 2: Digital services constitute the most dynamic trading sector

Services rely on trust

Most traditional services are so-called experience products or credence products. Their quality cannot be observed or tested before they are consumed, and sometime not even then. Imagine having your car repaired. Most of us don’t know what exactly is required to keep our car safe and in good repair. We need to trust the car repair shop. By the same token, we don’t know exactly what needs to be done to keep our teeth healthy, so we must trust that the dentist knows what she is doing. The dentist and the car repair shop in turn rely on a good reputation to attract customers.

Trust and reputation do not travel very far. To create a market for services beyond the local community, therefore, mechanisms to reassure consumers are needed. Standards are one such mechanism. Governments or business associations set the standards, license services providers, or certify that they comply with the standards. Note that while standards and regulations typically relate to the product for goods, standards relate to the provider in services markets.

Enter digital platforms. They have opened new opportunities for services traders all over the world, including SMEs from developing countries. Much has been said about platforms’ market power, dominance, and possible abuse of market power, but the fact remains that they, at their best, provide the digital infrastructure and not least the trust that SMEs need to thrive online. The consumer is assured that she will receive the product that she ordered at the right time to the agreed price and quality, while the seller is assured that the product will be paid for. However, despite the wealth of case studies of successful SMEs from the developing world thriving in global markets on digital platforms, a closer look at the statistics suggests that they do not make much of a dent in total services trade.

The recorded music industry: at the digital technology frontier

Recorded music demonstrates that a truly global digital market with low entry barriers and interoperable standards is possible. The industry is almost completely transformed to a digital format where streaming platforms with a global reach dominate. For artists, the barrier to entry on e.g., YouTube or TikTok is very low. From there, they can build an audience and move on to music streaming platforms such as Spotify, Apple Music, Deezer and others. Many artists also make their debut on these platforms. Underlying the music streaming supply chain is a host of industry standards and applications that ensure that recordings are tagged with an ID that contains information on all the involved intellectual property rights holders. The ID follows the recording in all its uses (streaming, radio, movies, video games, shopping malls, gyms, etc.), such that software applications – often powered by AI – that collect and distribute royalties to the rights holders, can trace the music in real time. Thus, with the help of AI-enabled applications, global markets are established where artists, big and small; mainstream, and niche; can build an audience and receive royalties.

Why are there not more digital services markets like the recorded music industry?

In principle, any digitally transformed service (e.g., software as a service, cloud computing, accounting, or radiology) can be traded seamlessly over the Internet in a similar manner as recorded music, provided safeguards are in place to protect safety, privacy, and security. However, in the average developed economy a couple of hundred occupations are subject to licensing. Regulation is typically not harmonized, and recognition of qualifications and standards are typically not automatic even when there is a mutual recognition agreement in place. The cost of complying with different standards in different jurisdictions may hence confine SMEs to the local market.

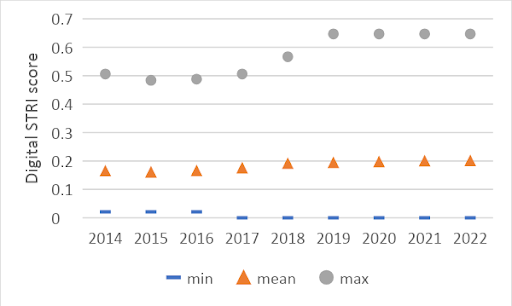

While tariffs and non-tariff barriers to international merchandise trade have declined steadily since the 1960s, trade restrictions on digital services have been rising since 2015 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Annual average Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (85 countries)

The rise may seem moderate, but it is going in the wrong direction, and estimates suggest that the change has reduced services trade by about 10% compared to a scenario where trade restrictions remained at the 2015 level.

The nature of the changes are new restrictions on cross-border data flows, data localization requirements and lack of pro-competitive regulation in telecommunications. The rationale for introducing such restrictions are security and privacy concerns, data sovereignty – and outright protectionism.

The idea that data are better protected if stored in a particular jurisdiction is challenged by experts. They maintain that a decentralized network is much better suited for protecting data than centralized data flows. Furthermore, local network providers typically have weaker capabilities to keep data safe than the leading global providers.

Data localization requirements may result in loss of access to cloud computing where they are applied. They may also encourage large firms to use private, parallel networks and VPNs. Widespread data localization requirements may even split the Internet into separate national or regional networks and loss of the global public good that the open and decentralized Internet has been.

Summing up, the digital transition of services has opened new opportunities for access to information, state-of-the art cloud services and market infrastructure that substantially reduce the need for SMEs to build up intangible capital in the form of trust and reputation before they enter new markets. Rather than undermining the open and decentralized Internet with data localization requirements, policy makers should focus on how regulation addressing legitimate concerns about privacy and security can be made interoperable in practice.

To download the 2023 edition of the Network Readiness Index, focused on the theme of trust in technology and the network society, visit https://networkreadinessindex.org/

Hildegunn Kyvik Nordås is a Senior Associate with the Council on Economic Policies. She also holds a position as visiting professor at Örebro University in Sweden and research professor at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) in Norway.